Historical Significance

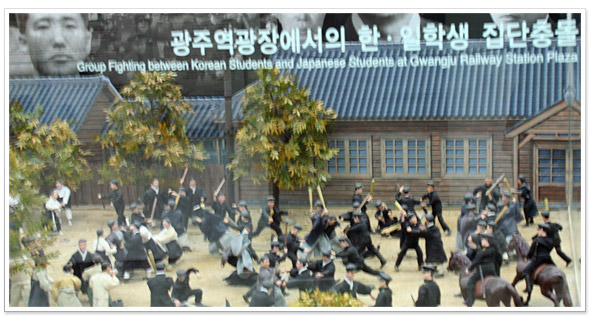

1. Explosion of the Gwangju Student Independence Movement

On October 30 1929, a fight erupted among Japanese students and Korean students, who commuted to and from Gwangju and Naju. As Japanese students attending Gwangju Middle School harassed a Korean girl, the Korean students attending Gwangju Normal High School saw this and protested. This led into a big fight involving students from both sides. Korean students, who experienced first-hand the exploitation and contempt of Japan, and Japanese students, who were rude and arrogant under the umbrella of Japanese colonial authority, always had a relationship for potential conflict, and as this continued to build up, it ultimately exploded.

Details of the Incident

- As the 5:30pm Gwangju-Naju commuter train arrived at Naju Station on October 30, 1929, Japanese students from Gwangju Middle School came out of the exit. They grabbed the hair of Park Gi-ok, Amseong Geum-ja and Lee Gwang-chun, who were students of Gwangju Girls’ Normal High School, and harassed them calling the Josen-jin. Park Jun-chae (cousin of Park Gi-ok) of Gwangju Normal High School got in an argument with them, which led to a big fight involving 50 Japanese students and 30 Korean students. Though the Korean students were outnumbered, they were higher in morale. Japanese police broke up the fight with a great deal of bias beating only on the Korean students. - There was a skirmish in the commuter train to Gwangju on October 31, but there was no big clash. However, another fight broke out in the commuter train to Naju in the afternoon. The Japanese conductor took Park Jun-chae and the Korean students to the second-class car, which were mostly of Japanese passengers, and cursed and criticized the Korean students.

- In the afternoon of November 1, prior to the departure of the commuter train to Naju, 30 students from Gwangju Middle School stormed towards Gwangju Station, and 20 students from Gwangju High School also came out and confronted each other. This was broke up by the teachers of the two schools, station employees, and police.

- Though there was no clash between the Korean and Japanese students on November 2, there was a tension in downtown Gwangju. The situation was grave where both Korean and Japanese studies had to move in groups in order to avoid being jumped.

2. First Demonstration in Gwangju

Since the Naju Station incident, clashes between Korean and Japanese students continued even under the patrol of the police and teachers, but this exploded on November 3. At about 11am, at Gwangju Station, students of Gwangju Normal High School clashed with Japanese students from Gwangju Middle School, which was followed by the joining of students from Gwangju Agricultural School and Gwangju Education School that resulted in street demonstrations.

The newspapers reported that the demonstrations on November 3 were the biggest incident since the March 1 Movement of 10 years ago. This shows that this large-scale protest was a huge case for not only the Gwangju area, but for those in other regions as well. As the press started to boil, the Government General recognized the severity of this case and banned its coverage. Now, based on the natural spirit, the student resistance for freedom of the nation and abolition of colonial slave education and national assimilation education began to develop from walkouts to street demonstration en masse.

Morning: Resisted with silence at the Meiji-setsu Day event

11am: Fight erupted in front of the Sugi-okjeong Post office

11am: Group fight between Korean and Japanese students, turning Gwangju Station into turmoil

Noon: Gathered at auditorium to discuss future measures, and unilaterally decided to go on demonstration

2pm: Students rallied and protested in downtown Gwangju for 3 hours

5pm: After breaking up, the group returned to their home

7pm: Began arresting the leaders

- November 4-

11am: Fight erupted in front of the Sugi-okjeong Post office

11am: Group fight between Korean and Japanese students, turning Gwangju Station into turmoil

Noon: Gathered at auditorium to discuss future measures, and unilaterally decided to go on demonstration

2pm: Students rallied and protested in downtown Gwangju for 3 hours

5pm: After breaking up, the group returned to their home

7pm: Began arresting the leaders

Gwangju Normal High School and Gwangju Middle School decides to close school for 3 days

Police arrested over 70 Korean students from the 4th to 11th and imprisoned 60 sending them to the prosecutor’s office

Police arrested over 70 Korean students from the 4th to 11th and imprisoned 60 sending them to the prosecutor’s office

Student demonstration spread to a large-scale anti-Japanese movement joined by citizens of Gwangju...

The demonstration was led by upperclassmen followed by lower classmen, and at the forefront were the mettlesome students of Kim Hwang-nam, Kim Bo-seob, Kim Sang-hwan, Kang Yoon-seok, and Kim Mu-sam. Outside of the school gate were waiting students from Gwangju Agricultural School who heard word from Choi Tae-ju, and welcomed them with a round of applause and joined the demonstrators.

As the demonstrator parade passed by, people cheered them and gave them sticks and firewood, and one person gave them about a dozen cherry-wood canes that he was trying to sell. A man who sold Chinese pancakes filled a basket full of pancakes, despite being poor himself, and shared them with the students, and other merchants gave what they could to cheer on the righteous uprising of the students.

Japanese oppression through closing of schools, arrests, and censorship

The school decided to close the school from November 4 to 6, but during that time, the police arrested a total of 72 students (48 from Gwangju Normal High School, 8 from Gwangju Middle School, 11 from Gwangju Agriculture School, and 5 from Gwangju Education School). Of them, they locked up 39 students from Gwangju Normal High School and 1 student from Gwangju Agriculture School and imprisoned them on grounds of violation of the security act.

Meanwhile, the Government General prohibited the press from covering the Gwangju Student Independence Movement. This was aimed at preventing the spread of student demonstrations. However, with press coverage being restricted, various rumors started to spread throughout the nation, which stimulated people and students of other areas, and thus acting as a factor for causing nationwide demonstrations.

3. 2nd Demonstration Movement in Gwangju

Being surprised by the resistance of November 3, Japan ordered a shutdown of schools until the 10th. Schools reopened on November 11, and on the 12th, students once again went on a large-scale demonstration criticizing the Japanese oppression and unfair treatment, and demanded the release of the imprisoned students. Despite the tight security of the armed Japanese police, the second demonstration was successfully held due to the organizational abilities of student movements that have been accumulated through walkouts and secret organization activities since the mid 1920s. The second demonstration in Gwangju organized a student resistance headquarters for organized execution of rallies so that it could go beyond being a simple street rally, to be able to be developing into a political and public fight with a clear purpose. And, this was the start line of the nationwide anti-Japanese national movement.

Nov 4/5 - Jang Jae-seong met with leaders of the Gwangju social and youth organizations and resolved to unfold more powerful organized struggles and expand it to nationwide student demonstration

Nov 7 - While discussing methods to expand the demonstrations of Gwangju throughout the nation with Bu Geon and Kwon Yoo-geun who came from Seoul, Jang Jae-seong inspected the Dokseohoe organizations of each school

Nov 10 - Representatives from Gwangju Normal High School, Gwangju Agriculture School and Gwangju Education School met at the home of Park Gi-seok and decided to proceed with the uprising on the 12th.

Nov 11 - 4 different manifestos printed; Oh Kwe-il prints approximately 1,000 copies of manifestos at the home of Park Gi-seok

Nov 7 - While discussing methods to expand the demonstrations of Gwangju throughout the nation with Bu Geon and Kwon Yoo-geun who came from Seoul, Jang Jae-seong inspected the Dokseohoe organizations of each school

Nov 10 - Representatives from Gwangju Normal High School, Gwangju Agriculture School and Gwangju Education School met at the home of Park Gi-seok and decided to proceed with the uprising on the 12th.

Nov 11 - 4 different manifestos printed; Oh Kwe-il prints approximately 1,000 copies of manifestos at the home of Park Gi-seok

Another large-scale demonstration towards Gwangju Prison using the class start bell on Nov 12 as a signal…

Nov 12 - As the morning class bell rang, students at Gwangju Normal High School all got up and left the school to downtown. Students spread the manifesto and yelled rallying cries and headed towards Gwangju Prison. They went in front of Gwangju Girls’ Normal High School and Gwangju Education School and cried for them to join, but the teachers stopped them from leaving. Students from Gwangju Agriculture School also cried ‘Let’s save our companion suffering in jail’ and rallied in the streets, but were forced to disband in front of Gwangju Normal High School.

-Map of 2nd Demonstration-

Morning: Resisted with silence at the Meiji-setsu Day event

11am: Fight erupted in front of the Sugi-okjeong Post office

11am: Group fight between Korean and Japanese students, turning Gwangju Station into turmoil

Noon: Gathered at auditorium to discuss future measures, and unilaterally decided to go on demonstration

2pm: Students rallied and protested in downtown Gwangju for 3 hours

5pm: After breaking up, the group returned to their home

7pm: Began arresting the leaders

-Map of 2nd Demonstration-

11am: Fight erupted in front of the Sugi-okjeong Post office

11am: Group fight between Korean and Japanese students, turning Gwangju Station into turmoil

Noon: Gathered at auditorium to discuss future measures, and unilaterally decided to go on demonstration

2pm: Students rallied and protested in downtown Gwangju for 3 hours

5pm: After breaking up, the group returned to their home

7pm: Began arresting the leaders

Gwangju Normal High School → Sugi-okjeong Post office → Gwangju Girl’s Normal High School →Gwangju Education School → Gung-dong → Gwangju Prison (disbanded)

Gwangju Agriculture School → Gwangju Normal High School (disbanded)

Gwangju Agriculture School → Gwangju Normal High School (disbanded)

After the second demonstration, resisted through Baekji Alliance and plans for 3rd demonstration

After the 2nd demonstration movement, Gwangju became quiet for a while with many student and social group leaders of Gwangju being imprisoned. However, the remaining students made the Baekji Alliance to continue their struggle. On January 9, 1930, 17 students of Gwangju Normal High School were expelled due to the Baekji Alliance, and on the 16th, the plan for the 3rd demonstration was discovered, and thus 48 more students were expelled. Thus, of the 460 sophomores, juniors and seniors, only 160 graduated. 15 students were also expelled from Gwangju Girls’ Normal High School due to the Baekji Alliance. A massive demonstration was also planned at the Gwangju Supia Girls’ School, but was discovered, and several leaders were arrested. The school was closed down indefinitely on January 31. Of the seven students who attended Gwangju Girls’ High School, which is a school for Japanese girls, Cha In-hee, Kang Jung-min, Choi Gong, and Jeong So-jin made a statement and withdrew from school.

Support of the Secret Organization Discovered, 200 Arrested

During interrogation of those arrested during the demonstration, the secret organization was discovered, and students involved in the Seongjinhoe, Dokseohoe and Sonyeohoe were imprisoned until January of the following year. Oh Kwe-il, Yoo Chi-oh and Lim Ju-hong were brought in from Tokyo. 200 of the arrested were students, which amounts to 1/5 of the 1,000 students in secondary school in Gwangju.

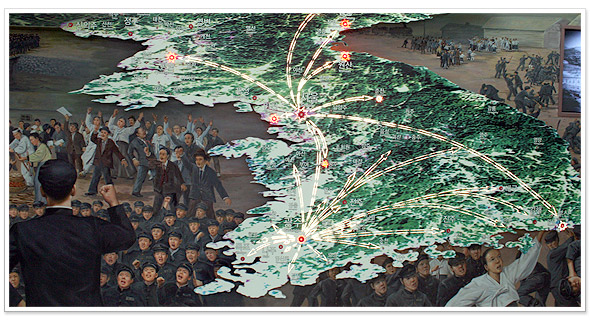

4. Spread to the Nation

The Gwangju Student Independence Movement first spread to Jeonnam and by linking with social and youth organizations such as the Youth Alliance, Shinganhoe and Geunwooheo, it quickly spread to the rest of the nation. Students in the Seoul area sympathized with the Gwangju Student Independence Movement and from early February 1929 to mid January 1930, they participated in large-scale student demonstration on two separate occasions, providing the opportunity for expanding student demonstrations nationwide.

Student demonstrations began to spread nationwide in full-fledge from early December 1929, focusing mainly on Gaeseong, Incheon, Wonsan, Pyeongyang, Hamheung and Gongju. From mid January 1930, it spread to schools in towns and villages as well, and was joined by students in normal schools. The method for resistance diversified from refusal to take tests, Baekji Alliance, leave of absence from schools, distributing manifestos, in-school demonstrations, street rallies, etc, and led to claims to gain national independence through face-to-face confrontation of the Japanese colonial rule authorities. The resistance of students did not stop in the nation, but spread overseas, and won the response of students in Manchuria, Japan, Siberia and the US, and became the greatest anti-Japanese national movement since the March 1 Movement.

Quickly spread to Jeonnam areas, Demonstrations rise in Mokpo and Naju

Japan not only restricted the press, but also closely monitored contacts by people or letters so that news of the Gwangju demonstrations could not spread to other regions. However, students in the Jeonnam area such as Naju, Mokpo and Hampyeong heard details of the incident, and engaged in rallies to respond to the Gwangju Student Independence Movement. They demanded the release of arrested students, denied colonial rule and cried for the independence and freedom of their nation.

1st and 2nd Demonstrations in Seoul, Spread manifestos in schools in Seoul starting with Gyeongseong Imperial University

Coming into December, the Gwangju Student Independence Movement moved its center stage to Seoul, while in parts, was spread to other provincial cities. During the night of December 2 to the morning of December 3, manifestos were distributed in major technical schools and middle schools in downtown Seoul, including Gyeongseong Imperial University. The distribution of this manifesto was made possible through secret contacts of Jang Seok-cheon and Gang Seok-won, who arrived from Gwangju, with that of the leaders of the Dokseohoe of each school. Japan made preparations to forcefully suppress this by dispatching horseback police in downtown Seoul, but starting with the walkout of the Gyeongseong Imperial University Normal High School 2, the spirit for resistance against Japan by students burned strong. 12,000 students joined the first demonstration and walkouts from the 2nd to the 13th, and 1,400 were arrested. The second demonstration from January 15 to 17 in 1930 was joined by over 3,000 students from 30 different schools. Like the first demonstration, it was organized in the manner of a unified resistance.

Walkouts and demonstrations occur consistently throughout nation, with lifting of prohibition of coverage, truths about student demonstrations spread nationwide

Student demonstration in Seoul that occurred on two separate occasions played a decisive role in the Gwangju Student Independence Movement spreading nationwide. Furthermore, with the lifting of the ban on press coverage on December 28, the truths of the student demonstrations in Gwangju and the resistance of different regions including Seoul became widespread knowledge throughout society. Aside from Seoul and Jeonnam, the student demonstration movement first occurred in Gongju. As the first demonstration in Seoul was in progress, it spread out in major provincial cities including Gaeseong, which was the closest to Seoul, as well as Incheon, Wonsan, Pyeongyang, Hamheung, Busan and Chuncheon.

Resistance of students was mostly in the form of walkouts, and due to early vacation, it lulled for a while. With school starting again in January, it restarted and developed greatly.

Demonstrations overseas, Student movements supported overseas such as in China, Japan, Russia and the US

The Gwangju Student Independence Movement did not stop within the nation, but actively spread out overseas. People sympathized with the Gwangju Student Independence Movement in Jiandao, Jilin, Harbin, Shanghai and Beijing in China, and in Tokyo and Osaka in Japan, and continued the activities of distributing manifestos, holding assemblies, and participating in manse rallies. In Russia and US, the movement was covered in the news, and they supported the students by criticizing the Japanese oppression.

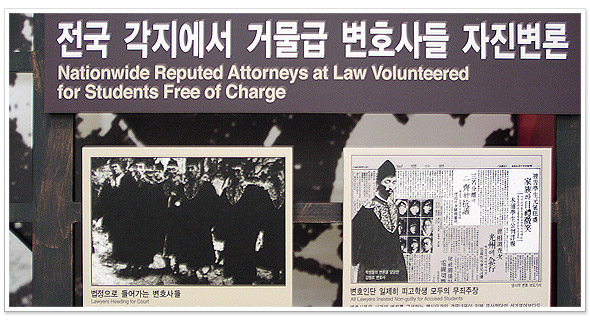

5. Legal Resistance

260 students were arrested and imprisoned in Gwangju for the Gwangju Student Independence Movement. 49 were arrested based on the Security Act, 38 were arrested for the relation with the Seongjinhoe, 90 for their relation with the Dokseohoe and 11 for the Sonyeohoe. Thus, a total of 173 (15 stood trial for both Dokseohoe and the Security Act) were forwarded to preliminary hearings. Japan changed its stance from attempting to downsize the incident, and began to claim that the Gwangju Student Independence Movement was caused by the instigation of communists and socialists, and the secret organizations that they made. This was a measure to treat student movements as communist and socialist movements in order to prevent it from spreading nationwide and in order to legitimize their tough suppression of it.

As if to prove this, of the 173 arrested, preliminary hearings for the 49 leaders of the demonstration arrested for their violation of the Security Act were concluded 3 months later on January 29, 1930. However, preliminary hearings for the violation cases of the Public Order Act on the Seongjinhoe, Dokseohoe and Sonyeohoe were completed 9 months later in July 1930. Putting aside torture and cruel treatment in prison, it shows just how bad violation of human rights was under colonial rule.

Big-shot lawyers from around the nation, Lawyers going to court

In the hearing of this case, lawyers living in Gwangju such as Seo Gwang-cheol, Kim Jae-cheon, Song Hwa-sik, Yoo Bok-young, Eoh Yoon-bin, Lee Jeong-sang, Ji Young-gu, and Song Tae-hwan, as well as other prominent lawyers from around the nation such as Kim Byeong-ro, Lee Chang-hwi, Kang Se-hyang, Lee In, Han Sang-eok, and Kim Wan-seob voluntarily came to Gwangju for their defense. The lawyers claiming the innocence of the students stated that the ‘seditious document contents’, which was the core of the crime related to the demonstrations, were much more moderate than the election campaign slogans of the Japanese parties, and firmly claimed the innocence of the students. However, the judges were not swayed and they sent all of the students to jail.

What is the reason that stronger sentences were given to those related to Seongjinhoe and Dokseohoe?

It was the downside of the Gwangju Student Independence Movement spread nationwide and even to Jiandao, and becoming the greatest anti-Japanese movement since the March 1 Movement. Japan feared that this student movement would spread to a national freedom movement of their colonial public of laborers and farmers. That is why they attempted to turn this case into a communist movement, while claiming that the Seongjinhoe and Dokseohoe were communist organizations.

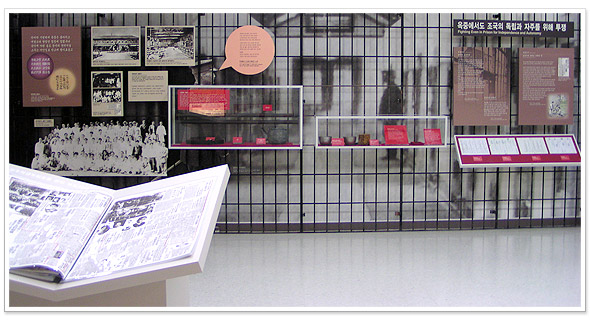

6. Resistance in Prisons

Students imprisoned due to the Gwangju Student Independence Movement and the Seongjinhoe, Dokseohoe and Sonyeohoe cases, as well as leaders of social organizations completely filled up the Gwangju Prison. The jailed students fought against the delay of trials, torture and cruel treatment of Japan and continued to resist using various personal methods such as cries and fasting. On March 1, 1930, the students tapped on the walls of their cells and simultaneously yelled ‘Independence manse’. On July 7, when a prison guard struck at Kim Bo-seob’s face with a sword saying that he was being too loud, the hundreds of students and other prisoners in the 150 cells in the five prison buildings engaged in a sit-in and chanted ‘Independence manse’ for three days. Whenever the students staged demonstrations in the prison, regular citizens also flocked the prison and responded to the in-jail resistance by urging them to stop the outrageous suppression. Whenever they were abused by Japan, the imprisoned students w

ould

shiver in rage and in order to defy the sadness of losing their nation by their death, they went on hunger strikes. As such fasting and hunger strikes continued, dozens of students went into critical conditions, and in panic, the prison authorities would inject food in them through the anal cavity to revive the students. Sometimes, they listened to the demands of the students as conciliatory gestures.

Memoirs in Jail Ⅰ- Spirit of the People that Blossoms in the Cell

Day by day, the number of student prisoners is increasing, and the cells are completely filled up, and now they are making temporary make-shift cells. There are various ways of torture as well. It’s commonplace to be beaten with a club. Sometimes they would place a piece of wood between the legs and make us get on our knees, and then step on us. They pierced underneath our fingernails with a sharp prick. They would fill some of us with water until our stomachs were ready to explode, some poured chili pepper powder in our noses, and sometimes, they would tie our two arms behind our back and hang us on the ceiling, which they named airplane torture. The most painful among them was electric torture. After making us lay down naked on the floor, they would tie our arms and legs so that we could not move them and pour water over us so that electricity would be more conductive in our body. When they connected a battery with our body, that pain was so bad that it is difficult to describe. When we see the pale faces

of our comrades who would return to the cell after such torture, our young hearts felt as if they were being torn apart. How could a human be so cruel to people? This is the tragedy of our people, a people without a nation. It was an unbearable living hell. When we heard students outside cry ‘Independence manse’ we would respond in our cells and yell manse together. If we get caught, the prison guards would drag us out and torture us to near death. No matter how often this was repeated the will of us students did not die. The most impressive part was that when a student tortured almost to death, the students in the cell would all come and massage and relieve their pains, acting as if we were all blood brothers. It is a sight that is hard to see without tears. In two weeks since being arrested, I was transferred to Gwangju Prison. In the middle of the night, they would use one handcuff to tie two people together and dragged them around.

As soon as we were transferred to prison, we changed into blue jail clothes and were attached with prisoner on trial numbers on our chests and pushed into the cells. All of the cells were packed down tight with students who arrived there before me. What I still remember is that the older students would stay up the night standing up so that I could rest comfortably. When the weather was cold they would take off their clothes and cover me and try to warm me up with their body heat. Looking back, the compassion the older students showed younger students at this time was the manifestation of a pure national spirit. The senior cell mates would try to comfort newcomers and told them how to receive interrogation from prosecutors.

(Park Jun-chae, ‘Shin Donga’ September 1969, from “Clash of Korean and Japanese Students that Escalated to Independence Rallies”)

Memoirs in Jail Ⅱ- In Cuffs to the Forbidden Room

The two were placed in solitary confinement as punishment. Chu Dang-seok went to solitary confinement in room 4. Yoo Chi-oh went to solitary confinement in room 3-16. Since this is a punishment, the two were placed in the hardest solitary confinements. In July it became hard to breathe in there and skin diseases worsened. The diseased parts oozed and it swelled up so much making it difficult to walk. Yoo Chi-oh asked the chief of the prison guard to change rooms, but the chief just retorted with a sarcastic remark. It was then. A Japanese guard named Goto suddenly appeared and without asking any questions, grabbed Yoo Chi-oh by his collar and dragged him out. There was a large concrete floor on the right side of the door. After dragging Yoo Chi-oh out there, Goto immediately repeatedly slammed him on the floor.

Goto has a fifth degree black belt in judo. At first, Yoo Chi-oh screamed, but soon after was knocked out cold. He was barely breathing and his limbs were shaking. Our comrades who were writing letters hurried to the door after hearing the grave screams and witnessed the hideous scene. They grinded their teeth in vexation.

“You butchers!”

Kim Min-hwan who had a strong voice, yelled as if to let everyone in the prison hears.

“Yoo Chi-oh was knocked out by the prison guard!”

The giant Chu Dank-seok continued to yell at his cell mates.

“Comrades, Yoo Chi-oh was beaten to death.”

The remaining comrades cried out loud. Kim Min-hwan who had a strong voice, yelled as if to let everyone in the prison hears.

“Yoo Chi-oh was knocked out by the prison guard!”

The giant Chu Dank-seok continued to yell at his cell mates.

“Comrades, Yoo Chi-oh was beaten to death.”

Cries started to erupt in different cells and in no time, it spread to all five prisons. The young lions within use began to roar. That was about 11:30 before noon. It was August 1, not even one month since the great resistance of the night of July 7.

At about 2pm, police reinforcements were requested to secure the outer perimeter of the prison. The prison directors’ meeting decided to suppress this, and began their suppression mission from 2pm.

Dozens of prison guards opened the doors to each prison and pressed down on the accused students in a cruel way. They cuffed the students and squeezed the chests with their jeongibok. Jeongibok is something like a leather vest. When it is soaked in water and tied across the chest, the leather would shrink as it dried and tightened so hard breaking some ribs and making it very difficult to breathe.

Yoo Chi-oh, who was dragged into the cell, woke up and started yelling not being conscious of how hurt he was. Immediately after, the cell door was opened and 4 or 5 guards rushed into the cell, twisted his arms and cuffed him. As the prison guard Goto laughed in delight after cuffing Yoo Chi-oh, Yoo kicked Goto as hard as he could in the gut. Goto let out an ‘ugh’ and slumped down on the floor. He was kicked in the penis.

Yoo Chi-oh got his revenge. But that was only for an instance. The remaining guards punched and kicked Yoo Chi-oh like a bunch of rabid dogs. They tied the jungibok across his chest and they put a leather belt in his mouth so that he could not scream and locked him up in the forbidden room.

The forbidden room is basically a dark room. It has no windows and no lamps, making it completely dark. Yoo Chi-oh was placed in this dark room having the jungibok squeezing his chest while being gagged and cuffed.

(Choi Seong-won, ‘Shin Donga’, June 1980, from “Gwangju Student Movement Resistance in Jail")

Torture Tools 1: Handcuffs, Leather vest, Leather belt

Japanese prisons assaulted the imprisoned students whenever they resisted by gagging them with leather masks, tying their hands behind their back and making them wear a leather vest that would constrict their chest when it dried, while locking them up in a room with absolutely no lighting.

Torture Tools 2: Piece of wood, watered chili pepper powder, prick

Gwangju Prison during the Japanese Occupation where students were imprisoned

The Japanese police mercilessly interrogated young students while committing brutality such as abusive language, beating, and electric torture.

Daegu Prison during the Japanese Occupation

Students arrested in connection with the Seongjinhoe and Dokseohoe were transferred and imprisoned here from November 1930 to January of the following year.

Rice with beans and salted radish soup that students ate while being imprisoned

After being perplexed with a sudden noise while sitting down, a yellow piece of fermented soybean on a nickel silver plate was pushed in through the hole on the bottom of the door. After that, a nickel silver plate was pushed in. There were a few pieces of cabbage floating in a clear soup, and there were a couple of thinly sliced radish floating in it. I think it was breakfast. I looked out the hole where breakfast was served through, and a man with a shaved head wearing a red prison uniform was looking towards me.

The yellow piece of fermented soybean looked to be about 90% beans and 10% millet, and I saw traces of brown rice. I laid the breakfast on the floor and stared down at it, and took a corner of the rice with bean and put it in my mouth. It seemed like sand. Trying to get help to swallow it, I took a spoon of the soup, but it made me nauseous because of its fishy and fat smell pierced my nose.

At lunch a yellow piece of fermented soybean and a small amount of salt was delivered.

(Choi Seong-won, ‘Shin Donga’, June 1980, from “Gwangju Student Movement Resistance in Jail)

A Game of Yut with the Rice and Bean

It was the most memorable meal during my imprisonment. While sharing the little food brought from an inmate from outside in our room, we looked to see if there were any messages from the outside and spent most of the day discussing the future prospects of the case and discussing state of affairs. Sometimes, we would dry the rice and beans to make yut and play a game of yut like kids while avoiding being caught by the guards to soothe our minds from despair.

(Park Jun-chae, ‘Shin Donga’ September 1969, from “Clash of Korean and Japanese Students that Escalated to Independence Rallies”)